Ever wonder how to make a clock from a paper plate? A skin cream from an avocado? A birthday cake out of fruit? Welcome to the world of “upcycling” and DIY (do-it-yourself) on Pinterest. Pinterest is a free website where users create virtual boards on which to post and share, or “pin” and “re-pin,” photos from outside sites and blogs that cover every topic from fashion and home décor to food and travel.

Pinterest users are slowly gluing, hammering, and knitting their way across the nation. As of March 2012, Pinterest was the #4 social network and #16 most trafficked website in the United States.[1] Founded in 2009, the site receives 11 million unique visitors each month, with an especially strong vistorship of women from ages 30 to 50 with children.[2] Sounds pretty phenomenal, right? Well, sorry to say Pinterest, but history tells us that this crafty movement is nothing new. Of course, it involved quite a different sort of “pinning.”

Pinterest, meet Godey’s Lady’s Book. Founded in Philadelphia in 1830, Louis A. Godey decided to target a growing American audience: women. Initially, Godey’s magazine featured a mish-mash of fashion plates (images), stories and poems gathered from other books and, quite fashionably, British magazines.[3] The practice of assembling a miscellaneous jumble of interesting tidbits was already common in other women-focused publications but Godey also added some original material. These sections were called “departments,” and offered all kinds of helpful home and health advice. [4] To a modern American audience, these suggestions can reveal drastic, er, differences in notions of cleanliness. One column, entitled “Washing the Hair,” advised against the fear of using water on the head because healthy hair requires daily washing:

“To prevent, therefore, [hair] becoming greasy and dirty, it ought to be washed daily with warm, but not too warm, soft water-to which, occasionally, a portion of soap will be a very proper addition.”

By the middle of the nineteenth century, the nature of education a woman should receive became an intense social contest but, many citizens—both men and women—feared that increased education for women would provide them with the capability to achieve economic independence, upsetting the strict Victorian family-based social structure.[5] The role of most middle class women, therefore, continued to remain centered on the home. Many women, however, used publishing to push the boundaries of female education within the limits of their domesticity. Sarah Josepha Hale was one such woman. Starting the Ladies’ Magazine in 1828¸ she sneered at the decadent, European fluff that filled other women’s literature and focused on publishing works by American, both male and female, writers.[6] In 1837, her magazine joined with Godey’s to create a publishing powerhouse. Focusing on broadening women’s minds, celebrating American literary talent, and trumpeting the values of thrift and prudence, Hall’s leadership of Godey’s brought its circulation to 150,000 before the Civil War and attracted writers like Edgar Allen Poe and Harriet Beecher Stowe.[7]

Directed toward the middle class, Godey’s became a cultural staple for many women. Those who could not afford the subscription on their own, would join clubs to share the magazine and the fee.[8] To be the most effective, dutiful, American sovereign over your home, you had to have Godey’s.

But this was no easy task. Let’s take a look at some “pins” from the Godey’s Lady’s Book.

Need to add some charm to your home with plants but having trouble locating those pesky earthen pots? Godey’s informs readers that “it may be interesting to know that plants generally grow better in tin fruit or meat cans.” Don’t have those either? Continue to read for instructions on how to make “tasteful trellises” for ivy and other plants using wire from an old hoop skirt.[9]

Outside the home, one also needs to be fashionable so, bring out those needles! Here is an example of four of the latest Paris Fashions for crocheted purses. To form the rings for the Eugene Purse (top left), merely crochet over steel rings and fill the center with a bead. [10]

Parties are always a stressful affair. To brighten up any children’s party, serve these little plum cakes from this simple, healthy recipe….

“Two pounds of flour, Half pound of sugar, Four eggs, Half pound of butter, Six spoonfuls of cream, One and a half pounds of currants. Mix butter and sugar to a cream, first washing the butter in rose-water, add eggs well beaten, then cream a little warm, then the flour and currants, the latter well washed and well dried; mix well, and make into small cakes, or bake in very small round tin pans in a tolerably hot oven. Frost the, and put a sugar toy on each one.”[11]

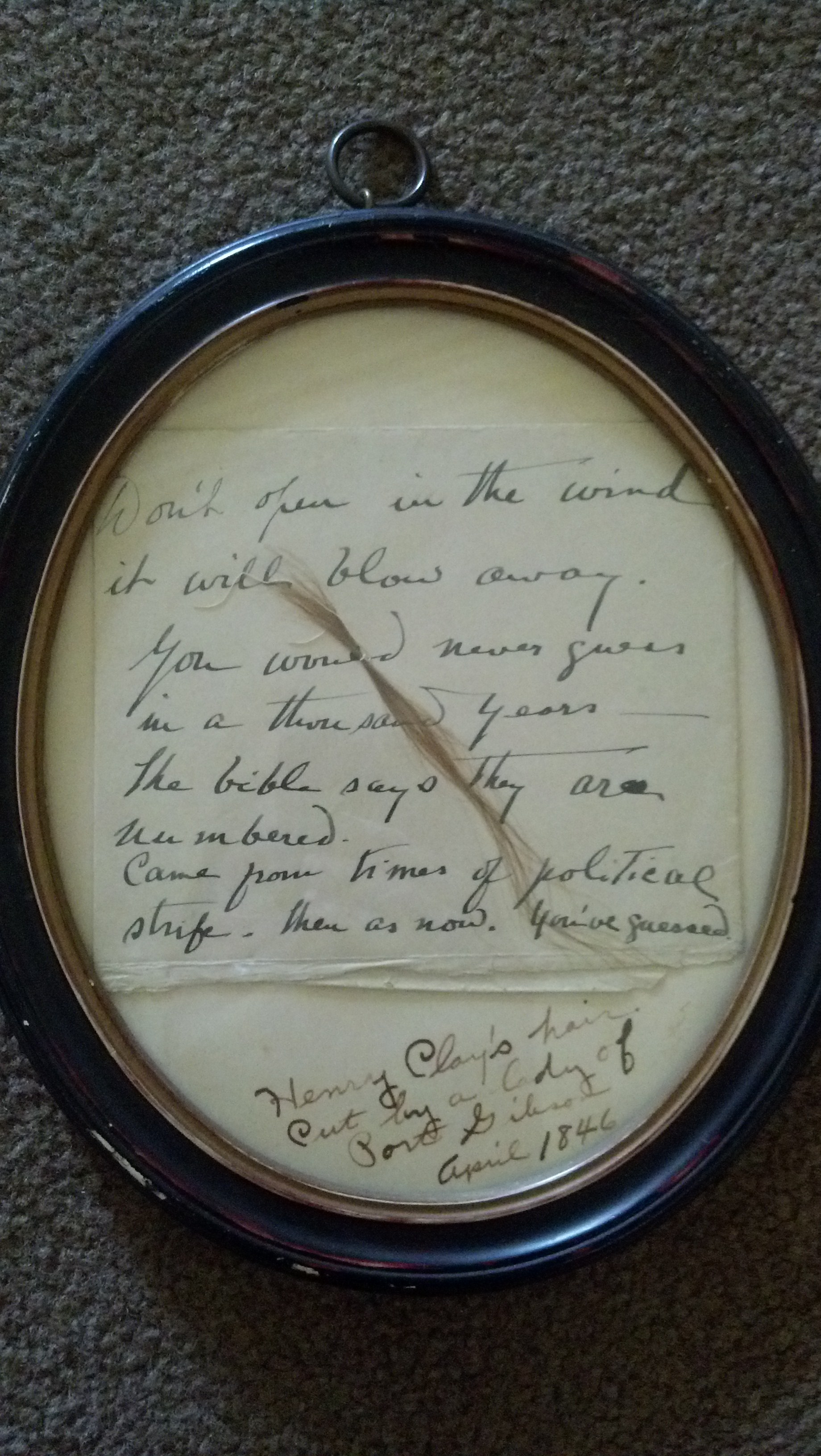

At the Lee-Fendall House, Godey’s would have been a major reference for Harriet Cazenove—the great granddaughter of Richard Henry Lee—as she moved into her new Alexandria home with her new husband, Louis, in 1850. Socially ambitious, the Cazenoves completed renovated the home to fit with the latest fashions and technology. Marble mantles replaced wood ones, a solarium (or conservatory) was added on the first floor, and the entire home was outfitted with new central heating, plumbing and gas lighting. So extensive were these renovations, the value of the home jumped from $3,000 to $12,000 between 1850 and 1852. To ensure the interior of her home equaled the impressive renovations, Harriet would have been aware of the advice emanated by Godey’s. Harriet’s plans for Lee-Fendall, however remained unrealized. In 1852, Louis died and left his new bride a widow. In 1856, Harriet decided to relocate and would rent out the Lee-Fendall House until it was confiscated in the Civil War by Union forces.

Need some more Godey’s? Check out next week’s blog post about Godey’s and Alexandria.

–Christina Regelski, Graduate Collections Intern

[1] Alicia Whitecavage et al., The Power of the Mighty Pin: Pinterest Examined (paper presented at proceedings of the 77th Annual Convention of the Association for Business Communication, Honolulu, Hawaii, October 24-27, 2012).

[3] Lawrence Martin, “The Genesis of Godey’s Lady’s Book,” The New England Quarterly 1.1 (1928): 65.

[5] Thelma M. Smith, “Feminism in Philadelphia, 1790-1850,” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 68.3 (1944): 248-9.

[8] Amy Condra Peters, “Godey’s Lady’s Book and Sarah Josepha Hale: Making Female Education Fashionable,” Student Historical Journal, Loyola University (1992-3).

[9] “Hints on Home Adornment,” Godey’s Lady’s Book (May 1880), in Accessible Archives (accessed November 2012).

[10] “Godey’s Latest Paris Fashions for Crochet Purses,” Godey’s Lady’s Book (December 1855), in Accessible Archives (accessed November 2012).

[11] “Recipes for Children’s Party. Little Plum Cakes,” Godey’s Lady’s Book (October 1879), in Accessible Archives (accessed November 2012).